Empowering Women Dentists in Pakistan: Changing the Landscape of Oral Health Sector

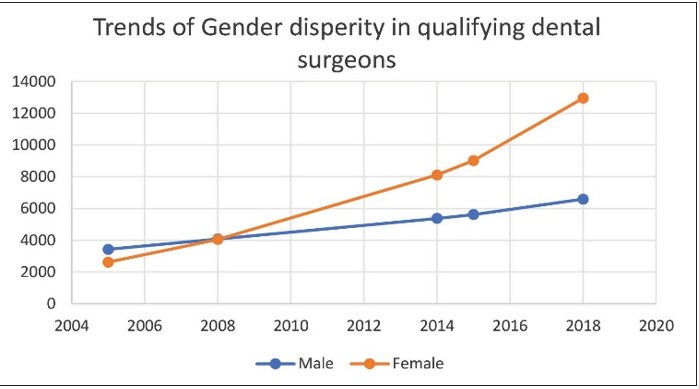

Prior to 1991; admissions for girls in medical and dental colleges of Pakistan was restricted to a very limited number of seats. However, in 1991, a decision of the Supreme Court of Pakistan let to an Open Merit Policy for admission in these colleges and the first such batch was taken in 1992. Last 25 years has witnessed a dramatic change in gender landscape of the medical profession in general and dentistry in particular. Today, there are more than two female dentists for every male dentist in the 28,736 odd dentists registered in the country.

Under the open merit rule, female presence dominates the dental colleges. However, the downstream effect of this changing scenario of trained health manpower / womanpower is that of a leaking pipe. On one hand there is an increased female enrollment in dental schools; and on the other hand, a very few of them continue to pursue this career.

In 2014, Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC) decided to implement a 50/50 quota for boys and girls based on their finding that only 50% 0f the women health professional take up their careers further; and that because of this trend the shortage of working health

personnel persists. This decision was, however, challenged in the court of law and withdrawn.

It is extremely difficult to ascertain labor market outcomes since limited data exists. The very best population or representative surveys such as Labor Force Surveys are not appropriate to understand this market.

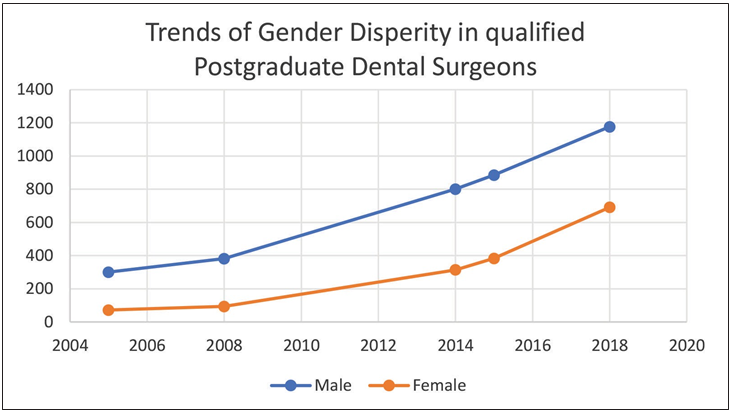

However, an even more elite sub-group of post-graduate enrollment, specialists and teaching professionals can be used to determine labor market outcomes of this segment of labor force. If postgraduate qualification is taken as a proxy measure for advancement in professional career; it has been seen to date that only 5% of the females compared to 20% of male dentists have postgraduate qualifications.

The most widespread explanation is that most women dropout from pursuing a career after getting their BDS degrees as they are not interested in specialization or a career; and their BDS degree is being used to find a better marriage match. This phenomenon needs to be seen in light of social biases and cultural practices of the country. Multiple influences can be identified that hinders/stops a female from taking decisions that influence their workstyle. This includes social and familial control over women’s decision to pursue a career; their traditional economic dependence on men; and restrictions on their mobility that determines their choice of career.

Globally, a vast majority of women dentist are involved in private practice of general dentistry; as this route gives them the flexibility of time once they start a family. Yet, here in Pakistan the small minority of women dentist who wish to pursue a career seek employment and there are only a handful of female dentists who own practices. It has also been noted that the women in dentistry seek employment soon after graduation or after their kids have started to go to school. They seek morning jobs as these would not interfere with their family routine. However, majority of the private practices have evening only sessions. Recent years have seen a high migration of professionals among the males of the country, therefore, today more women are in search of income making opportunities in the job market. Lack of professional confidence has also been sighted as one of the reasons fresh and returning graduates do not take a plunge in private practices. A recent study sponsored by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan shows that that on average only 59% of graduates perceived themselves as competent to practice dentistry. The perceived competency level varied from 17% to 98%. On the other hand, the study elaborates that almost 60% dental graduates declared themselves incompetent in 84 competencies which were agreed upon to be ‘very essential,essential or good to know by dental experts. (Self-Perceived Competency of Dental Graduates: Evaluation of Dental Institutions’ Performance in Pakistan 2015)

For fresh graduates; 75% of whom are women – there are no jobs or career development opportunities. The public sector has low priority for oral health care; infrastructure improvement is not on the card. There is no national or provincial oral healthcare policy or program. The sporadic dental cover presently available in some health care facilities only in the mornings with little or no equipment, instrument and material support.

After government the biggest employers are the private dental colleges; each employing 25-40 graduates. With 49 dental colleges in the country, new colleges are no longer a viable option; so few will come up in the remaining part of the decade. Existing Private sector is financially out of reach for majority of the population and practices are out for austerity measures.

On one hand, Pakistan has experienced an exponential growth in the middle and lower middle-income segment. It has been declared as an emerging market for healthcare facilities. Government is giving incentives to provide affordable health care to the population. While on the other hand, Dentistry is concentrated in 10 districts of the country and that too in the affluent areas. Dentistry has evolved as

a profession of the elite, with 90% of the dentists are concentrating on 10% of the population that can afford high end dentistry.

Despite the phenomenal growth in the number of dental professionals, multiple reports indicate that nearly 80% of all adults of Pakistani have experienced some dental problem in their lifetime; and that more than 90% of all dental disease remains untreated. Scientific reports also indicate that majority of middle and low income groups tend to go to unqualified or low-end professionals; which in majority of the cases lead to further complications and these people are always prone to secondary infections including Hepatitis C. In the middle of all this there are no new opportunities being created for the graduating dentists, majority of whom are made up of women. These women culturally lack entrepreneurial mindset and confidence to venture into practice of dentistry; and like other women of the country lack ownership of productive resources.

Establishing a dental practice involves a fair amount of capital which families would not invest as culturally they do not trust their women to establish a business of their own. Similarly, formal financial establishments of the country generally do not accommodate women credit needs; commercial banks disregard women clients due to their preconceived assessments on women creditworthiness as majority of them depend on men for collateral in the form of property, high cost of transaction on small loans, and difficulties in establishing a woman borrowers trustworthiness. Today, the gender gap among the medical doctors of the country has diminished; while, there are two female dentists for every male dentist in the country. Yet, only 23% of countrys working doctors and dentists are women. If only 50% of these out-of-profession female doctors and dentists are mobilized, 70 percent health issues of people especially of the low-income group of the population can be resolved. We as dental professionals may lead many of these efforts, but we cannot do it alone. Government, business leaders, insurance companies, health care professionals and individuals all have stake in this and must work together to get better dental care to the millions of Pakistanis who do not receive it.

The quickest way to do it would be to mobilize the out of profession ladies by incentivizing their return to the profession; providing them opportunities for the same; empowering them to look after the communities they serve; thereby, changing the landscape of oral health sector in Pakistan for the better.

It must be realized that today we are in the middle of what the most uncertain and challenging decade for dentistry. How we respond to the problem will determine to the future of the profession in Pakistan.