Provision Of Basic Dental Care To The Pregnant Women Enrolled In Vitamin D Supplementation Trial

ABSTRACT: It’s likely that the participants enrolled in a study are diagnosed with certain health conditions that are unrelated to the main research objective but otherwise are fairly treatable and manageable; this poses a challenge to the investigators. It becomes more relevant when the trial subjects have no health insurance or if trial is being conducted in a community where basic health facilities are not readily available. Here, we report the dental services rendered to the participants enrolled in a community based, double blind, randomized controlled trial that was conducted atdistrict Jhelum. The pregnant women n=85 were inducted. After the completion of trial, a total of 109 subjects (trial participants and their attendants) were examined at the study site using a mobile dental unit at base camp. Scaling was the most frequent service (n=42, 38.5%) rendered followed by oral hygiene instruction (n=39, 35.7%) and extractions (n=20, 18.3%) in subjects.

CLINICAL RELEVANCE: A service component when introduced to a community based study, it does not only ensure participants’ interest, but adds value to the research.

HOW TO CITE: Khan FR, Ahmed T, Hussain R, Bhutta ZA. Provision of basic Dental Care Tothe Pregnant Women enrolled in Vitamin D Supplementation Trial.

J Pak Dent Assoc 2015; 24(2):104-106.

INTRODUCTION

Among all study designs, randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) is considered as the gold standard[1]. Researchers put substantial effort in designing and conducting RCTs to generate high quality scientific evidence that helps to shape the future of the healthcare[2]. It’s likely that the subjects enrolled in a clinical trial are diagnosed with certain health conditions that are unrelated to the main research objective but otherwise are fairly treatable and manageable; this poses a dilemma to the investigators. It becomes more relevant when the trial is being conducted in a community where basic health facilities are extinct or at least not readily available.

The good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines for trials suggests that “during and following a subject’s participation in a trial, the investigator/institution should ensure that adequate medical care is provided to a subject for any adverse events, including clinically significant laboratory values, related to the trial”. However, provision of care for a health condition that is relatively “unrelated” to the primary objective of the study is not discussed in thatguidelines[3]. Here, we report the dental services rendered to the participants enrolled in a community based, double blind, randomized controlled trial that was conducted atdistrict Jhelum. The pregnant women from 12-16 weeks of gestation were inducted. The objective of the primary study was to determine the effect of oral vitamin D supplementation on the pregnancy outcomes. The detailed results are published elsewhere[4].

METHODOLGY

A total of 85 pregnant women were recruited in the study that was duly approved by Aga Khan University Ethics review committee (AKU-ERC,ref# 147-Ped-ERC2010) and trial protocol was registered at the clinicaltrials.gov bearing ID# NCT014221225

A large proportion of the females enrolled in the trial had some dental problems but their access to the professional dental care wasrestricted. There was no qualified & registered dental practitioner in that area. This compelled them to travel to over hundred miles to get oral care at any setting that has any reasonableinfection control practices.Both the access and the financial affordability of professional dental care werequestionable. Moreover, during prospective assessment of the subjects on regular time points, the trial participants started to expect some form of dental treatment. Although, it was not part of the original study protocol, but we discussed this within our team to provide some help to the participants so that a community service elementis added to our research. This made it possible for not only the trial participants but their immediate household to get basic dental care.

A mobile dental operatory that was originally acquired for Aga Khan Health services in Northern areas of Pakistan and was attained at the trial site. The permission was obtained to use that mobile dental operatory (with all instruments, accessories, materials along with an autoclave sterilizer) for delivering the baseline dental care to the study participants at the community trial site.A dentist and a dental assistant (both full time employed at university) visited the PindDadan Khan for 10 days. The project office of the women and child health division at trial site was used as the base camp to install the dental operatory.The treatment delivery visit was confined to serve the pregnant females already registered in the trial with no intentions to carry out any new research.Study participants were brought into the office by the project transport.

RESULTS

We planned to deliver required oral care to 85 females

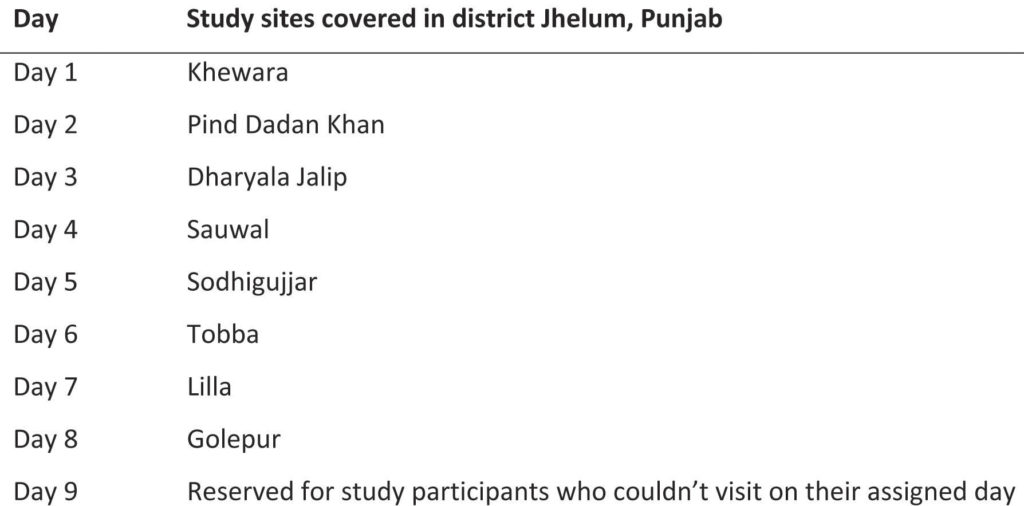

Table 1: Geographical distribution of study participants and dental care plan

Table 1: Geographical distribution of study participants and dental care plan

Basic dental care to pregnant women in a trial

out of which 70 turned up. However, 26 males were also seen. These males were the immediate family members of the study participants. There were 13 other females

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of the Participants

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics of the Participants

examined who were either local residents or were close relative (sister or sister in law) of the study participant andwere accompanied with the participants. Thus, a total of 109 subjects were attended.

DISCUSSION

Pakistan is a resource constraint country. The model of health care in rural districts of the country is such that public hospitals are already over-burdened. Limited funds, deficiency of health care staff and long distances between clusters of population and health care facility makes the accessibility of care a challenge. Moreover, the health insurance or any third party coverage is nonexisting in the underdeveloped areas. This makes the provision of clinical care to the participants already enrolled in a randomized trial an uphill task. Although, investigators, ethics review committee and the data safety monitoring units, all work as a team to design and take up appropriate measures to ensure safety of the participants but it’s not uncommon for anystudy participant to develop a health condition that is albeit manageable but is somewhat unrelated to the primary research objective.

In the present study, scaling was the most frequent service (n=42, 38.5%) that was being offered. This reveals that hygiene related periodontal problems were prevalent in the sample. Those who presented with minor periodontal deposits were advised oral hygiene instruction and education on tooth brushing and flossing (n=39, 35.7%). Extractions under local anesthetic were done on 20

(18.3%) subjects. There were 8 subjects (7.4%) who did not gave consent for any intervention primarily because of the fear that they will get any injection during treatment. Their decision was respected and no intervention carried out on this subset. The most important limitation in the course of this exercise was our inability to offer dental restorations (fillings). We didn’t carry any mercury disposal system with us; so amalgam restorations were not done. Similarly, lack of polymerization light guide tip prevented us from carrying out resin based composite fillings too.

There was a warm response among the local residents who requested contacted clinical trial project office to get their families examined but it was not possible to expand the services because of limited resources including time available to us. However, providing the baseline dental care to the under privileged community was an excellent gratifying experience.

CONCLUSIONS

We inferred that whenever possible, a service component should be added to the community based studies. This not only ensuresparticipants’ interest, but adds value of community service to the research and above all, it rewards the investigators with a satisfying experience.

GRANT INFORMATION

The main study was supported by a grant from Pakistan Initiative for Mothers and Newborns (PAIMAN). The USAID-funded Pakistan Initiative for Mothers and Newborns (PAIMAN) project has served various districts in Pakistan. Professor Zulfiqar A. Bhutta is the recipient of the grant.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors acknowledge the kind help of Dr Sajid Soofi and Dr Atif Habib at the Women and Child Health Division, Aga Khan University and Mr Didar Alam at the Nutrition Research Laboratory of the Aga Khan University, Karachi for the conduct of this study

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

Dr Zulfiqar Ahmed Bhutta received the grant, planned and supervised the main vitamin D study.Dr Farhan Raza Khan did the periodontal assessment of pregnant females and wrote this manuscript. Dr Rabia Hussain contributed by doing the multiplex inflammatory biomarkers analysis for development of periodontitis among study participants.Dr Tashfeen Ahmed did the statistical analysis of study data and supervised of the dental aspect of study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Brit Med J 1996; 312: 71-72.

- Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Evidence based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. J Am Med Assoc 1992; 268: 2420-2425.

- http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ ucm073122.pdf. Page 14.

- Khan FR, Ahmad T, Hussain R, Bhutta ZA. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on the periodontal status of pregnant females- A randomized clinical trial. (unpublished data) J Periodontol.

- Khan FR, Bhutta ZA. Study of Vitamin D Supplementation on Improvement of Gums Health. www.clinicaltrials.gov: Identifier: NCT01422122.